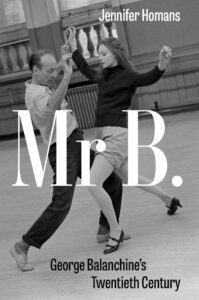

Mr. B: George Balanchine’s 20th Century by Jennifer Homans

How did you conduct your research?

Balanchine has been one of the greatest intellectual, emotional, and spiritual encounters of my life. The research was an intense decade-long journey that really began a lifetime ago when I was a teenager and first set foot in a dance studio, saw and performed Balanchine’s dances, and watched him work. How could I have known then that the project of knowing him would take me to archives and places and people in Russia, Georgia, and across Europe and America; into the history of war, art, music, literature, jazz and African American dance, all of which influenced him greatly; into philosophy, Orthodoxy, Sufism, exile, the Cold War, and so much more.

I was especially interested in the testimony of dancers and I interviewed over 200 people who had worked with or known Balanchine and the other supporting characters in the book. His dances did not exist without dancers, and their presence—physical, emotional, and intellectual—profoundly shaped his life—and my account of him.

But testimony and memory are not history, and I also did extensive archival research in Russia, Georgia, and in cities across Europe and America. Balanchine himself destroyed the evidence of his life as he went, and recovering him meant reading everything that was left, from letters, sketches and musical scores. to credit card receipts and passport applications. I also walked Balanchine’s path, and followed him to dance studios, theaters, and museums; hospitals, Orthodox churches, restaurants and hotels; places where he loved, and places where he wept.

I read what he read: Cervantes, Goethe, Shakespeare, Ovid; Pushkin, Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Chekhov, Gogol, Bulgakin; Mysticism, Neoplatonism, Spinoza, Sufism; I studied art that he drew on, from Russian Icons, to Renaissance painting, and the surrealists. I listened: to Bach, Mozart and Tchaikovsky; Stravinsky, Ives, Hindemith, Xenakis. And of course, I watched, and danced, his dances.

How far do you think the twentieth century shaped Balanchine’s being and relationship to his work?

Profoundly. I subtitled the book “George Balanchine’s 20th Century” because he absorbed into his dances the century he lived through. He experienced WW1, the Russian Revolution, WW2 and the Cold War; he was in Berlin and Paris in the 1920s, and landed in NY in 1933 in the middle of the Depression. He lived through hunger and dispossession; statelessness and exile; epidemics and illness (he should have died of TB). He worked on Broadway, in Hollywood, and staged opera, theatre and the circus, and in 1948, he cofounded the New York City Ballet where, with his dancers, he made some of the strangest and most glorious dances to grace the modern stage.

I also subtitled the book “George Balanchine’s 20th Century” because his dances were his 20th Century—the one he created in art.

It took me 600 pages to answer this question, which is truly at the heart of the Mr. B.

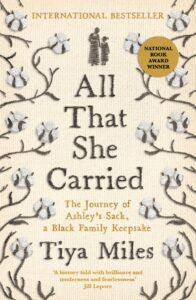

All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake by Tiya Miles

How did you conduct your research?

All That She Carried is the first book on Ashley’s Sack, a unique artifact of the African American experience that illuminates key themes in this history, such as enslavement, loss, family, motherhood, love, perseverance, artistry, and migration. While other scholars have conducted research on the sack or used it as an illustration of Black family separation or of radical visual self-representations, no one had before produced a full-length study of the artifact or its keepers. Researching the sack presented me with numerous and at times seemingly insurmountable challenges because the embroidered sack is the only known record of Rose and Ashley’s story. However, this documentary deficit proved to be an unexpected benefit because it necessitated the construction of a different kind of history, which I have come to think of as history in a poetic mode. This mode does not reject scholarly methods of historical investigation. Rather, it enlarges them by looking for a range of atypical sources and by offering interpretations that reach for deeper understandings of the experiential and emotional facets of historical life. The lack of traditional sources pushed me to think creatively about the relationship of early Black history to the archives, innovative archival practices, and experimental ways of narrating histories of Black women and other marginalized groups. Because the documentary record for this family is scanty prior to 1900, genealogical and biographical links in the book are speculative. In the book, I expose the inability to recover full and precise information about this family and many families that suffered enslavement, and I dwell on this difficulty as a meaningful part of the story.

How is the theme of memory illuminated in the book?

In the book, I consider how objects—especially objects explicitly linked to stories—have a special capacity to contain and revive memory in human experience. The delicate embroidery on the sack represents a family memory of sorrow and resilience that might have been lost if not for the carrying capacity of that bag. While doing this work, I was conscious of how my book about the sack is itself an object that helps to preserve public memory about a collective past. I was taken by this sense of doubling, or echoing, in the project.

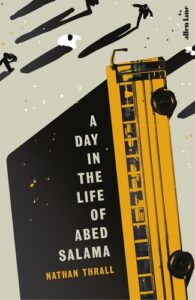

A Day in the Life of Abed Salama: Anatomy of a Jerusalem Tragedy by Nathan Thrall

How did you conduct your research?

The seed of this book was planted on the day of the school bus crash, which took place not far from my home in Jerusalem. The kindergartners and teachers on the bus live just two miles from my apartment, but behind an imposing, 8-meter-tall concrete wall that encircles their community. Cut off from the heart of the city in which they grew up and crammed into a dense urban ghetto, they are forced to drive on narrow, dilapidated streets with no lanes, sidewalks, or police presence, and to wait in long lines at a military checkpoint to get to their schools, jobs, and hospitals—all of this in plain view of the elegant campus of Israel’s most prestigious university. The consequences of segregating and neglecting these people came into sharp relief when tragedy struck on the other side of the wall. Like many residents of Jerusalem, I drove by that walled-off enclave every week, hardly noticing it. But after the accident I couldn’t stop thinking of the children and the families who share this city with me, and what a different world they have been forced to live in. It wasn’t until years later, when I had the time to devote myself to writing a book, that I began in-depth research on the collision, sifting through police reports, court documents, and audio and video recordings. My research expanded from there, as I spoke to more and more Palestinian families whose lives were destroyed by the event, and to Israeli Jews whose own paths intersected with it. It was important to me that the book tell the personal stories of both Palestinians and Jews; finding the right characters took considerable digging. But the truth is that many of the most important discoveries came by chance. A close family friend turned out to be a distant relative of one of the parents, Abed Salama. As soon as I met Abed and heard his story, I knew he would be at the center of this book. Over the next four years, he and I spent so much time together that I came to feel like an honorary member of his family. Abed and a number of other characters shared their rawest emotions with me, in some cases revealing thoughts, feelings, and memories that they had kept from their own spouses. I knew I had a tremendous responsibility to do right by the trust they bestowed on me.

How does your book interweave the stories of Jewish and Palestinian characters with the journey of Abed and Milad, the book’s protagonists?

The book tells the story of Abed and his son Milad, but also of a teacher who sacrificed herself to rescue her students, a bystander who heroically entered the burning bus to pull out dozens of children, a settler paramedic who had witnessed unimaginable horrors in the past but was haunted and traumatized by the scale of this tragedy, and two desperate mothers who each hoped to claim the same severely injured boy as their son. By delving into the lives and backgrounds of the characters, the book ended up ranging far beyond the immediate present of the accident and forming a kind of intimate, multigenerational history of Palestine and Israel as refracted through these individuals’ families and memories. Once I decided that the book would essentially follow the chronology of the day, the structure began to fall into place. One of the great challenges was to interweave two different timelines: on one hand, the day of the crash and the order in which each protagonist intersected with it; on the other, the deep history of Israel-Palestine.