Blood Memory: The Tragic Decline and Improbable Resurrection of the American Buffalo by Dayton Duncan and Ken Burns is the companion book to the upcoming two-part 4-hour PBS documentary titled The American Buffalo, premiering October 16 and 17. In making the documentary eighteen extended on-camera interviews were conducted, totaling in more than thirty hours, only portions of which could be fit into the four-hour film. This book draws extensively from the fuller transcripts of what was said in those interviews.

“We saw the first train of cars that any of us had seen. We looked at it from a high ridge. Far off it was very small, but it kept coming and growing larger all the time, puffing out smoke and steam; and as it came on, we said to each other that it looked like a white man’s pipe when he was smoking.”

– Porcupine, Cheyenne

“In the ripeness of time, the hope of humanity is realized. This continental railway will bind the two seaboards to this one continental union like ears to the human head; [and plant] the foundation of the Union so broad and deep that no possible force or stratagem can shake its permanence.”

– William Gilpin, governor of Colorado Territory

*

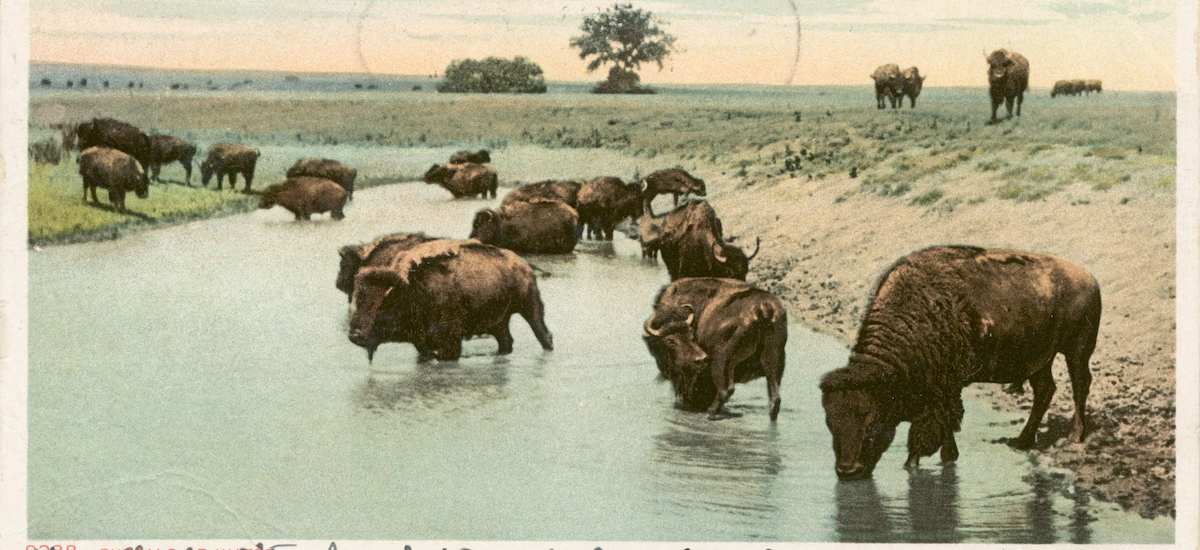

The cataclysm of the Civil War tore the nation apart, causing the death of 750,000 men, more than 2 percent of the population. But when the war was over, and the North and South were reunited, Americans set out with renewed energy to unite the nation, East and West. To do it, they began extending railroads to span the continent—opening up vast areas beyond the Missouri River for homesteaders, creating easier access to distant metropolitan markets for crops and cattle, and servicing the demands of boomtowns that had sprung up after gold discoveries in the mountains of Colorado and Montana. In the Great Plains, the pace of change quickened as never before, and on a scale that made the spread of the horse culture in the 1700s and the arrival of steamboats in the 1830s pale by comparison. Native people called this newest agent of transformation the “Iron Horse.”

“What we see happening in the Great Plains, in the years after the Civil War, is different from what had been going on earlier,” said the historian Andrew Isenberg. “In the beginning of the nineteenth century, there’s trade between Native people and Euro-American fur traders. They’re consuming beaver pelts and they’re consuming bison robes. That’s very different from this industrial society in the post–Civil War period that encounters the Great Plains—an industrial society that is much more interested in consuming resources.”

As the Union Pacific pushed west across Nebraska, heading toward California, the Kansas Pacific aimed for Denver from Kansas City, piercing into the heart of the buffalo range of the central Plains. To feed the hungry crews laying track, the railroad company hired an ambitious and flamboyant twenty-one-year-old Union veteran, paying him $500 a month to keep them supplied with the meat from twelve buffalo a day. His name was William F. Cody. By his own account, he killed 4,280 bison during a year and a half to fulfill his contract. Within a few years—thanks in part to his talent for self-promotion and his incorrigible habit of embellishing his actual exploits—he would become one of the nation’s most famous westerners, but under a different name: “Buffalo Bill” Cody.

Within a few years—thanks in part to his talent for self-promotion and his incorrigible habit of embellishing his actual exploits—he would become one of the nation’s most famous westerners, but under a different name: “Buffalo Bill” Cody.Homesteaders along newly completed sections of the railroad lines also discovered that bison could be useful for getting ahead in life. Some hunted buffalo to feed their families or to supplement their meager incomes by hauling buffalo meat to railroad depots for passengers to feast on. Nearly all of them gathered the ubiquitous dried manure piles (called “buffalo pies” or “buffalo chips”) to burn in their stoves and fireplaces for cooking their meals and keeping their sod houses warm.

Railroad passengers often amused themselves by firing at the herds that sometimes slowed a train’s movement. “[It] was the greatest wonder that more people were not killed, as the wild rush for the windows, and the reckless discharge of rifles and pistols, put every passenger’s life in jeopardy,” wrote Elizabeth Custer, traveling to join her husband, an Army officer stationed in Kansas. To publicize its progress across the Plains, the Kansas Pacific even promoted excursion trips for passengers eager to see—and shoot at—the buffalo they were sure to encounter. “In estimating the number,” a satisfied customer reported, “the only fitting word was ‘innumerable;’ one hundred thousand was too small a number, a million would be more correct.”

A church group from Lawrence organized a special two-day outing to raise money for the congregation. Three hundred people signed up—and brought along a cornet band. On the second day, they came upon a herd, according to an account by E. N. Andrews:

“[The buffalo] kept pace with the train for at least a quarter of a mile, while the boys blazed away at them without effect. Shots enough were fired to rout a regiment of men.

Ah! See that bull in advance there; he has stopped a second; he turns a kind of reproachful look toward the train; he starts again to lope a step or two; he hesitates; . . . a pail-full of blood gushes warm from his nostrils; he falls upon the right side, dead.

The train stopped, and such a scrambling and screeching was never before heard on the Plains, except among the red men, as we rushed forth to see our first game lying in his gore.

[I] had the pleasure of first putting hands on the dark locks of the noble monster who had fallen so bravely Then came the ladies; a ring was formed; the cornet band gathered around, and . . . played “Yankee Doodle.” I thought that “Hail to the Chief ” would have done more honor to the departed.”

Such excursion trips made good copy for newspapers and may have helped the railroads advertise their progress across the Plains, but they did not reduce the bison population appreciably, Elliott West said: “There are these images of people shooting bison from railroad cars, and, as you hear with the overlanders, that’s sometimes given as a reason for the decline of the bison. Well, of course not. I mean, were you really going to kill that many animals shooting at a moving target from a train?” More significant was the way the railroads accelerated the encroaching settlement of eastern Kansas and Nebraska, which were no longer reserved as part of Indian Territory. Cattle drives had begun, trailing thousands of cows (some carrying a disease called Texas tick fever) from Texas north to reach the railroads, for shipment to eastern stockyards and slaughterhouses. The buffalo range contracted some more.

In only one way did the bison seem to welcome the arrival of the Iron Horse. Along the new tracks, telegraph lines were strung from wooden poles. The buffalo—always looking for a rough surface to rub up against on the treeless Plains—found them to be perfect scratching posts. They toppled so many poles, the company decided to attach bradawls, a metal tool with sharp points, to dissuade them. It didn’t work. “[The buffalo] would go 15 miles to find a bradawl,” The Leavenworth Daily Commercial reported. “They fought huge battles around the poles containing them, and the victor would scratch himself into bliss until the bradawl broke, or the pole came down. There has been no demand for bradawls from the Kansas region since the first invoice.”

They toppled so many poles, the company decided to attach bradawls, a metal tool with sharp points, to dissuade them. It didn’t work.When the white man wanted to build railroads, or when they wanted to farm or raise cattle, the buffalo protected the Kiowas. They tore up the railroad tracks and the gardens. They chased the cattle off the ranges.

The buffalo loved their people as much as the Kiowas loved them.

There was a war between the buffalo and the white men. The white men built forts in Kiowa country . . . but the buffalo kept coming on, coming on. Soldiers were not enough to hold them back.

Even before the Civil War’s end, Native tribes had successfully resisted the relentless incursions onto their homelands, and the Army had built forts in response. Now, more forts were established, and more troops were dispatched to man them. Buffalo Bill Cody signed up to act as an Army scout and to help supply the posts with buffalo meat. Officers and enlisted men spent some of their idle time firing at bison for pleasure. At one fort in Kansas, the captain issued an order: “Item No. 1. Members of the command will, when shooting at buffaloes on the parade ground, be careful not to fire in the direction of the Commanding Officer’s quarters.”

George Armstrong Custer had been a celebrated cavalry hero during the Civil War. His impulsive bravery in a series of battles made him, at the age of twenty-two, the Union’s youngest general. Eleven horses had been shot out from under him. Posted now at Fort Riley, Kansas, with the newly formed Seventh Cavalry, he rode out one day to kill his first buffalo. Galloping up next to a bull, he aimed his revolver—and somehow managed instead to shoot his horse through the head. On foot, bruised, and totally lost, he had to be rescued by his own men. Adding to the humiliation, the dead horse was one he had taken from Confederates at Appomattox, named Custis Lee, and given to his wife. He had to explain to Elizabeth that he had killed her favorite mount.

The soldiers were there to deal with what was called “the Indian problem,” not to hunt buffalo for sport. For Custer and all the other Army officers, vanquishing the western tribes was proving frustratingly difficult. Native American warriors attacked railroad survey crews and road gangs, occasionally even derailed trains. The Army’s retaliations proved ineffective—and sometimes disastrous for both sides. The Plains seemed aflame with skirmishes, raids, and occasional massacres. In 1867, Congress decided to try a different approach. Delegations were dispatched to pursue “the hitherto untried policy of conquering with kindness.”

That October, more than five thousand Kiowas, Comanches, Arapahoes, and Southern Cheyennes gathered at Medicine Lodge Creek in Kansas to hear a proposal from U.S. officials to end the violence on the southern Plains. The treaty council nearly ended before it began. The Indians learned that on the way, and despite explicit orders from their officers, some soldiers had killed buffalo for their tongues and left the carcasses to rot. “Has the white man become a child, that he should recklessly kill and not eat?” a Kiowa chief asked. The offending soldiers were placed under arrest, and the negotiations commenced.

The government proposed that the United States be allowed to build railroads to the Colorado gold mines and encourage settlement north of the Arkansas River. The Native tribes would move onto reservations in what is now southwestern Oklahoma, where they would be supervised by agents drawn from Christian denominations like the Quakers. They would receive food and supplies for thirty years, be provided schools for their children, and be taught how to farm. The Kiowa chief Satanta objected:

“I love the land and the buffalo and will not part with it. I want you to understand what I say. Write it on paper. I don’t want to settle. I love to roam over the prairies. There I feel free and happy, but when we settle down we grow pale and die. A long time ago this land belonged to our fathers; but when I go up the river I see camps of soldiers on its banks. These soldiers cut down my timber; they kill my buffalo; and when I see that, my heart feels like bursting. I have spoken.”

“Do not ask us to give up the buffalo for the sheep,” Ten Bears of the Comanche added. “Do not speak of it more: I was born upon the prairie, where the wind blew free, and there was nothing to break the light of the sun. I was born where there were no enclosures, and where everything drew a free breath. I want to die there, and not within walls. I have hunted and lived over that country. I lived like my fathers before me, and like them, I lived happily. So why do you ask us to leave the rivers, and the sun, and the wind, and live in houses?”

The peace commissioners promised that, south of the Arkansas River, non-Indians would be prohibited from settlement, and the tribes could exclusively continue hunting there “so long as the buffalo may range thereon in such numbers as justify the chase.” Though not every band of each tribe was represented, the treaty was signed and sent to Congress. The Kiowa calendar for that year showed an Indian and a white man shaking hands near a grove of trees.

A year later, farther north at Fort Laramie on the Platte, a similar treaty was signed by some of the Lakota Sioux. In exchange for the government’s abandoning its Army forts in Wyoming’s Powder River country, an expansive Great Sioux reservation was created, encompassing half of present-day South Dakota, including the sacred Black Hills. The treaty also contained a clause stating that the Lakotas were free to hunt outside the reservation—so long as there were buffalo.

General William Tecumseh Sherman, now in command of the Army in the West, reluctantly agreed to the hunting concession. “This may lead to collisions,” Sherman wrote his brother, “but it will not be long before all the buffaloes are extinct near and between the railroads.”

General Sheridan,

As long as buffalo are up on the Republican [River], the Indians will go there. I think it would be wise to invite all the sportsmen of England and America . . . for a Grand Buffalo hunt, and make one grand sweep of them all.Until the buffalo and consequent[ly] Indians are out [from between] the roads, we will have . . . trouble.

General William T. Sherman

Early on the morning of January 13, 1872, a train pulled up to the Union Pacific railroad platform at North Platte, Nebraska, flying the flags of the United States and Russia, and carrying a special passenger. Grand Duke Alexis Alexandrovich, the fourth son of Czar Alexander II, was in the midst of a goodwill tour of America that had already created a media sensation with massive parades and elegant receptions in cities up and down the East Coast. He had come west to hunt buffalo.

His host, Lieutenant General Philip Sheridan, was overseeing the elaborate details for the outing. Troops of soldiers, even a cavalry band, had already set up “Camp Alexis” a day’s ride south, with a walled tent, floored and carpeted for the guest of honor, and wagon-loads of provisions that included plenty of champagne. Buffalo Bill Cody was on hand, having selected a campsite he was sure would be near a buffalo herd. Cody had recently guided a number of newspaper owners and wealthy businessmen on what was dubbed in the press as the “millionaire’s hunt” in the same area. To accompany Russia’s young aristocrat, Sheridan selected George Armstrong Custer, now a lieutenant colonel. Despite his disastrous first encounter with a buffalo, Custer had developed a love for chasing game across the Plains and had also hosted hunts for English nobility, journalists, and influential easterners. “Buffalo hunting,” he said, is “the most exciting of all American sports.”

The hunt began on January 14—the Grand Duke’s twenty-second birthday—and Alexis was accorded the privilege of the first kill. Equipped with a pearl-handled revolver, made especially for him by Smith & Wesson, and after some coaching from Custer, he rode up alongside a bull and fired several shots. But the bull was only wounded. In his own embroidered account of the moment, Buffalo Bill placed himself at the center of the action, claiming that Alexis was riding his horse, Buckskin Joe:

I rode up to him, gave him my old reliable [rifle] “Lucretia” and told him I would give him the word when to shoot.

At the same time I gave old Buckskin Joe a blow with my whip, and with a few jumps the horse carried the Grand Duke within about ten feet of a big buffalo bull.

“Now is your time,” said I. He fired and down went the buffalo.

Alexis jumped down, cut off the buffalo’s tail as a souvenir, and “let go a series of howls and gurgles like the death song of all the foghorns and calliopes ever born.” In celebration, bottles of champagne were distributed to everyone. Later, when the Grand Duke shot a second bison, out came a second round of champagne. “I was in hopes that he would kill five or six more before we reached camp,” Buffalo Bill recalled, “especially if a basket of champagne was to be opened every time he dropped one.”

That night, Sheridan presented his guest with another gift. With the promise of thousands of rations of flour, sugar, coffee, and tobacco, he had lured Chief Spotted Tail and nearly six hundred members of his Lakota tribe to join them. The next day, nine of the Lakotas took part in the hunt. One of them, named Two Lance, demonstrated how Indians could bring down a buffalo with a single arrow. Two Lance’s passed clear through the animal’s chest. He then presented the arrow to the Grand Duke as a parting remembrance of his adventure.

“I think I may safely say,” Sheridan proudly reported to Washington, that the hunt “gave more pleasure to the Grand Duke than any other event which has occurred to him since he has been in our country.” Alexis took the train to Denver for a grand ball, then for another hunt with Custer in eastern Colorado Territory. On their way through Kansas, he shot a bull from the window of his passenger car. Later, the Grand Duke and Custer posed for portraits together. Not to be forgotten, Cody had copies of the photograph reproduced—with an image of himself superimposed to make them a trio.

“Now is your time,” said I. He fired and down went the buffalo.As Alexis headed home to Russia, Buffalo Bill left the Plains for New York City. A dime novel about him had been turned into a play—and the breathless newspaper accounts of his time with the Grand Duke had made him even more of a celebrity. Once he saw the gaudy melodrama, he decided to join the cast. If money was to be made playing Buffalo Bill onstage, he might as well get some of it himself.

__________________________________

From Blood Memory: The Tragic Decline and Improbable Resurrection of the American Buffalo. Reprinted with permission from Knopf. Copyright © 2023 by Dayton Duncan & Ken Burns.